Record-breaking Atlantic hurricane season ends

The extremely active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on 30 November with a record-breaking 30 named tropical storms, including 13 hurricanes and six major hurricanes. There were 12 landfalling storms in the continental United States.

The extremely active 2020 Atlantic hurricane season officially ended on 30 November with a record-breaking 30 named tropical storms, including 13 hurricanes and six major hurricanes. There were 12 landfalling storms in the continental United States.

This is the most storms on record, surpassing the 28 from 2005, and the second-highest number of hurricanes on record.

2020 marked the fifth consecutive year with an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

An average season has 12 named tropical storms, six hurricanes, and three major hurricanes. Named storms have winds of 64 km/h (34 knots or 39 mph) or greater. Hurricanes have wind

s of 117 km/h (64 knots or 74 mph) or greater. Major hurricanes are Category 3 and above on the Saffir Simpson scale, with maximum sustained winds of 178 km/h (111 mph) or greater.

Even though the official hurricane season has concluded, tropical cyclones may still develop.

Tropical cyclones are one of the world’s biggest natural hazards. WMO’s Tropical Cyclone Programme, now marking its 40th anniversary, works to protect life and property and socio-economic well-being through global and regional coordination and cooperation.

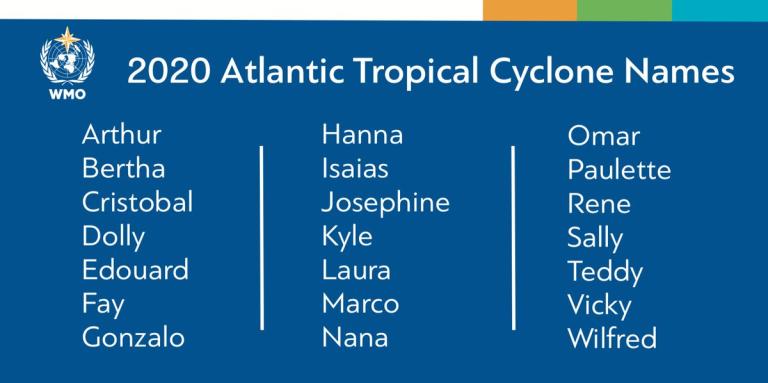

The 2020 season got off to an early and rapid pace with a record nine named storms from May through July, and exhausted WMO’s 21-name rotating Atlantic list with Tropical Storm Wilfred (September 18).

For only the second time in history, the Greek alphabet was used for the remainder of the season, extending through the 9th name in the list, Iota.

Iota made landfall in Nicaragua on 17 November as a powerful category 4 on the Saffir Simpson scale and impacted an area which had been hit by category 4 Eta less than two weeks previously, with hundreds of casualties. It was the first time on record, the Atlantic has had two major hurricane formations in November at a time of year when the season is normally winding down.

WMO Regional Association IV Hurricane Committee will review the season at its annual session in May 2021 and will consider which names should be retired.

Accurate Predictions

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s seasonal hurricane outlooks accurately predicted a high likelihood of an above-normal season with a strong possibility of it being extremely active.

This increased hurricane activity is attributed to the warm phase of the Atlantic Multi-Decadal Oscillation (AMO) — which began in 1995 — and has favored more, stronger, and longer-lasting storms since that time. Such active eras for Atlantic hurricanes have historically lasted about 25 to 40 years.

An interrelated set of atmospheric and oceanic conditions linked to the warm AMO were again present this year. These included warmer-than-average Atlantic sea surface temperatures and a stronger west African monsoon, along with much weaker vertical wind shear and wind patterns coming off of Africa that were more favorable for storm development. These conditions, combined with La Niña, helped make this record-breaking, extremely active hurricane season possible.

Relationship with Climate Change

In addition to the record number of hurricanes, another noteworthy aspect was that we also saw yet more examples of very rapid intensification and very slow-moving hurricanes, both of which have recently been linked to climate change. This is according to one of the world’s foremost experts on tropical cyclones, Jim Kossin, an atmospheric research scientist at NOAA’s Center for Weather and Climate, part of NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI).

In 2020, to date, there have been a remarkable ten hurricanes that rapidly intensified (Hanna, Laura, Sally, Teddy, Gamma, Delta, Epsilon, Zeta, Eta and Iota)—some of which underwent explosive intensification—and two hurricanes that practically stopped moving as they made landfall (Sally on the Gulf Coast and Eta in Central America). All of these storms had the potential for causing great damage and loss of life because they were so strong and they lingered for so long.

“The main culprit for the hyper-activity this year was warmer-than-average ocean temperatures. This is also the main reason for the longer-than-average season and the numerous rapid-intensification events,” said Dr Kossin. “The frequency of rapid-intensification events has increased over the past four decades, and this increase has been linked to climate change.”

The length of the hurricane season increases by about 40 days per degree Celsius of warming (the season starts about 20 days earlier and lasts about 20 days longer, on average). But the link to climate change for this is not as clear because our understanding of how and why hurricanes form is not as strong as our understanding of how and why hurricanes intensify, said Dr Kossin.

Dr Kossin is a lead author with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Fifth and Sixth Assessment Reports) and was long involved with the former WMO Expert Team on Tropical Cyclones and Climate Change.