Glaciers and Ice Caps

Glaciers and ice caps are persistent bodies of ice that gradually flow downhill due to gravity. Formed by the accumulation and compression of snow over time, glaciers and ice caps are found primarily in polar regions and high-altitude mountain ranges like the Himalayas, Alps and Andes.

Vue d'ensemble

A glacier is a large accumulation of mainly ice and snow, that originates on land and flows slowly through the influence of its own weight. Glaciers are found on every continent. They exist in many mountain regions and around the edges of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. There are more than 200 000 glaciers in the world, covering an area of around 700 000 km2 (RGI, 2023). Glaciers are considered as important water towers, storing about 158 000 km3 of freshwater (Farinotti et al., 2019). Glaciers are a source of life, providing freshwater to people, animals and plants alike.

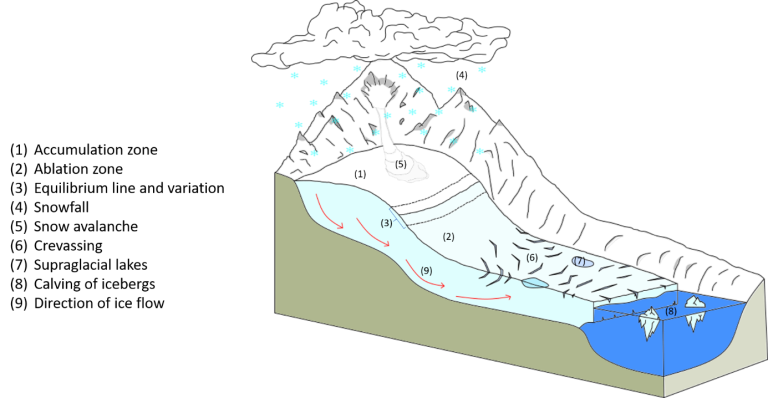

Glaciers gain mass through accumulation processes such as snowfall and sediment deposition and lose mass through ablation processes such as melting and evaporation. When accumulation outpaces ablation, glaciers have a ‘positive mass balance’; when ablation exceeds accumulation, glaciers have a ‘negative mass balance’. Glaciers flow downhill due to gravity. This movement occurs slowly, typically in meters per year, though some glaciers, like the Jakobshavn Glacier in Greenland, have been recorded to flow at speeds of over 40 meters per day (Joughin et al., 2014).

Glaciers vary widely in type and size. Piedmont glaciers spread into bulb-like lobes on flat plains, while tidewater glaciers terminate in the sea. Other types, such as mountain and hanging glaciers, are harder to distinguish from each other. Glaciers are often characterized by features such as crevasses (cracks formed by glacier flow) and moraines (debris deposited at the margins of glaciers during glacial retreat). Glaciers range in size from small masses of around 100 meters to hundreds of kilometers in length. According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), glacier thickness averages about half the width of the glacier’s surface.

Ice caps are large dome-shaped masses of glacier ice that largely obscure the surface topography whilst covering areas of less than 50 000 km2. Unlike glaciers, ice caps flow outwards in all directions (glacier flow is constrained by surface topography).

Impact

Glaciers and ice caps are critical for sustaining ecosystems and human livelihoods. They provide essential meltwater runoff during dry seasons, supporting drinking water, agriculture, industry, and clean energy production, making these frozen reservoirs vital for global water resources. Climate and cryosphere changes, however, are disrupting the water cycle, altering the amount and timing of glacier melt, causing knock-on impacts on water resource availability while also contributing to sea-level rise.

As glaciers continue to shrink and snow cover diminishes, less water will be available for communities, particularly in seasonally dry regions. Increased competition for water resources is expected, with regions like China, India, and the Andes among the most vulnerable. Glaciers that have surpassed their “Peak Water” point—the stage at which meltwater runoff reaches its maximum—will gradually provide decreasing contributions to downstream water supplies, intensifying challenges for water security.

Over the past century, despite representing only 0.5% of global land surface area, glaciers have contributed more to sea-level rise than the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. Between 2000 and 2023, glaciers are estimated to have lost an average mass of approximately 273 billion tonnes per year, which is equivalent to approximately 0.75 mm per year of global sea-level rise (The GlaMBIE Team, 2025).

The continuous retreat of glaciers signals the growing impacts of global warming and creates new hazards while intensifying existing ones. For example, melting glaciers are increasing the risk of hazards such as glacier lake outburst floods, ice avalanches and glacial debris flows, posing dangers to local and downstream communities. However, risk assessments are often not possible due to an absence of data (IPCC, 2019). Therefore, increased observation of the cryosphere is critical for effectively forecasting the impacts of cryosphere-related hazards.

The implications of cryospheric changes extend beyond local communities, underscoring the need for robust monitoring, improving the understanding of future changes, together with coordinated global efforts to mitigate risks and adapt to the evolving challenges posed by the cryosphere.

Réponse de l'OMM

The WMO supports international efforts to monitor glaciers and ice caps.

In 2022, the WMO published the first globally coordinated guide to the Measurement of Key Glacier Variables, within the WMO Guide to Instruments and Methods of Observation (WMO No 8, Volume II), available in its six official languages. It provides an extensive assessment of current practices on monitoring and reporting glacier data, and it supports the definition of standards for data reporting.

The WMO Third Pole Regional Climate Centre Network (TPRCC-Network) prepares and disseminates regular assessments of glacier changes in the Hindu Kush Himalaya region.

The WMO community is advocating for systematic monitoring of critical atmospheric conditions on or in the proximity of glaciers, e.g. temperature, precipitation, and snow accumulation, in support of increasing the capabilities to predict changes in the glacierized basins, thus informing adaptation policies for the benefit of populations downstream.

The WMO is collaborating with other research networks, e.g. Mountain Research initiative, the Third Pole Environment to improve the access to existing datasets on glaciers and the surrounding environments, to support other large-scale initiatives, e.g. climate reanalysis.

Glacier monitoring remains a priority to better understand their role in the Earth’s systems and to mitigate the challenges posed by their retreat.

The International Year of Glaciers’ Preservation 2025 is one of the critical opportunities to increase the awareness of climate change driven changes in the mountain snow and ice and frozen ground underneath them, their critical role in the ecosystem, and how their disappearance changes livelihoods.

Greater awareness in the policy domains are needed to support dedicated action to address the sources of anthropogenic climate change while preparing populations to adapt to unavoidable changes.