Sustaining Engagement in an Online Course for Trainers

Note: This article is adapted from a chapter in the upcoming publication, WMO Global Campus Innovations

- Author(s):

- By Patrick Parrish, WMO Secretariat

The urgent response to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the need to reduce in-person events, has required rapid conversion to distance learning delivery options to maintain capacity development goals. However, the WMO Education and Training Office (ETR) recognized the value of distance learning long before the recent dramatic changes to workplaces.

The First World Meteorological Congress in 1951 adopted Resolution 10 authorizing “WMO to participate in the United Nation Programme of Technical Assistance for Economic Development of Underdeveloped Countries.” Thus, developing the competencies of Members to promote common, high-level service delivery standards has been a cornerstone of the work of WMO throughout its first 70 years. Capacity development to enhance the knowledge and skills of staff members in the National Meteorological and Hydrological Services (NMHSs) is one of the key activities of WMO technical department. Over the last decades, ETR courses to train trainers and the adoption of distance learning have permitted WMO to extend the reach and depth of its capacity development.

The importance of training trainers

The WMO Executive Council (EC) began designating Regional Training Centres (RTCs) in the 1960s to identify, then support, local centres to offer learning opportunities for developing core qualifications and to enhance service delivery. RTCs ensured that Members in developing countries had training opportunities that aligned with their expectations, in local languages and in closer geographic proximity. The train-the-trainer courses were developed to help RTCs and to support national trainers. The early courses aimed to share the latest scientific and technical knowledge so that regional and national training would be in line with international standards in science and services.

However, as instructional technologies evolved and competency-based approaches to teaching were demonstrated as the most effective for developing operational knowledge and skills, a new emphasis arose for the courses for trainers. In the early 2000s, the courses became targeted to helping trainers develop a working knowledge of practices that included the application of cognitive and constructivist learning principles, as well as competency-based approaches for improving learning outcomes. Learners would actively practice new skills in addition to receiving the required background information. These courses involved an average of 20 to 25 participants attending a two-week residence course.

In 2014, after codification of these learning principles for the WMO competency requirements for education and training providers provided in the Compendium of WMO Competency Frameworks (WMO-No. 1209) and publication of the Guidelines for Trainers in Meteorological, Hydrological and Climate Services (WMO-No. 1114), closer alignment and more complete coverage of the competencies were expected. Developing training competency is related to more deliberate consideration in making the decisions required for effective training design. This required a longer course, one that offered practice in carrying out the entire training planning process, which was not feasible in classroom mode due to limited time, logistics and cost. It also suggested the need to reach more participants, with new trainers taking on that role each year.

Motivation to deliver training online

Going online meant that we could reach more in the training community. This is partly due to the elimination of a physical location and travel costs. But online learning also simplifies delivery in other languages because facilitators can be located anywhere, and second language facilitators and learners can take more time to read and compose responses, sometimes using machine translation as an aid. There are many motivations for increasing distance learning (DL) approaches including:

- increased reach and equal opportunity

- greater sustainability of learning through broader impacts and opportunities for longer-term interaction with learners

- lower costs and lessened disruption to work due to travel

- opportunities for early intervention prior to training events and ongoing connection afterwards, during application of new knowledge and skills on the job

- aids to evaluating the impacts of training

- facilitating the dissemination of learning to others through, for example, preservation of learning resources

- flexibility for learners and trainers who need to meet family and work responsibilities

- higher relevance through immediate connection to the learners’ job environment

- increased empowerment and independence of learners, which build skills for lifelong learning.

Starting with the first online course, the average number of students earning certificates of completion increased to 37 per offering—a 60% increase—at a cost reduction of at least 85%. In the nine offerings conducted from 2014 to 2019, in English, Russian, French and Spanish (with the aid of WMO RTCs), a total of 333 certificates of completion were granted. When one considers that each of these 333 participants directly impacts the learning of many others in the training they offer, we can assume that 1000s will have benefited from the improved training practices.

As will be shown, the course has quite rigorous requirements for certificates of completion. This is contrary to the assumptions of many that online approaches cannot be as rigorous as classroom learning. And while many expected that it would be difficult to sustain engagement in a comprehensive online course, especially in regions with challenges to Internet access, the number of completions has been quite gratifying. The most recent offering, the 2020 WMO Online Course on Education and Training Innovations, linked to an upcoming Global Campus publication, while different in format and content, covered much of the same ground. Over 100 certificates of completion were issued for the course, which was in many ways even more demanding than prior courses.

A final motivation for going online was to promote the use of online learning and new online tools for engaging learners, such as discussion forums, simulations, games and various media. The course has exposed many more trainers to the possibilities of online learning, and provided many examples of active learning approaches, which has influenced their training practices in general. More online training translates to meeting more WMO Members’ capacity development needs. Indeed, the annual statistics from RTCs show that online learning has nearly doubled in recent years, from 600 students in 2014/2015 to 1128 students in 2016/2017. As the testimony of RTC staff has confirmed, part of this increase can be attributed to exposure to the WMO Online Course for Trainers.

The usual fears associated with converting a classroom experience to an online environment were felt—losing engagement, lower knowledge and skill gain, lower enrollments, etc. But none of these fears turned out to be justified. In fact, by redesigning the course from scratch as an online experience, we gained in each of these areas.

Format of the course

The WMO Online Course for Trainers is almost entirely asynchronous, meaning it does not rely on facilitators and participants being online at the same time. They access the course website, view resources, contribute to discussions and participate in activities at times available to them. This not only provides significant flexibility for participants and facilitators to fit the course into their schedules, but it allows the course to be run with students in any time zone. While the offerings usually focus on one or two regions, participants come from nearly all regions for some. Language is a stronger boundary than geography. The 2018 French-language course attracted participants and facilitators from five WMO regions, and the 2020 English-language course had participants from all six WMO regions.

One down-side with the asynchronous approach is that participants and, especially, their managers, may give the course less attention than a residence course. While the participant nomination form asks that the Permanent Representative to WMO agree to a 6 to 8 hour per week work release during the course, our experience is that only about 50% receive this time. Most simply fit the course into their personal time, after-hours and on weekends. Many also respond that 8 hours is not enough time to complete the work, partly due to it not being in their mother-tongue. Nonetheless, most do complete the course.

The course has evolved and improved over time. The 2019 edition took a narrower focus on blended learning while the 2020 edition focused on innovations in education and training. The last full competency-based versions of the course (2017 and 2018) were offered in 9 one-week units, grouped into 3 modules, with two breaks of at least one week between modules (allowing for holidays and time to catch up on assignments). A Pre-Course preparatory orientation session of about two weeks is also offered as an ice breaker, allowing participants and facilitators to get to know one another—establishing important social engagement and commitment.

The course units are mapped to the WMO competency framework for education and training providers (WMO-No. 1209). Like with all competency-based training, course completion indicates that participants have had practice and feedback on applying the underlying skills and demonstrated that they have acquired the required background knowledge, full competence is within their reach.

Engagement strategies

A weeks-long online course requires careful design to maintain the engagement of participants. While many are concerned that distance learning inevitably leads to high dropout rates, the WMO Online Course for Trainers has over a 75% completion rate. Furthermore, the majority of the remaining 25% leave the course in the first few weeks, or do not start at all. While no thorough analysis has been conducted to determine the primary reasons for leaving or not starting, the number who leave before or during the first weeks indicates that the format is unexpected by some of those who register. Even though clearly described in announcements, some may be curious to see what the course looks like before deciding not to learn online. After the first 2 weeks, the percentage of those that do not finish is very small, less than 10%, often due to conflicts with work assignments. Nonetheless, this 10% gained from their partial participation and no investment was lost in the offering.

How does the course keep an average of 37 participants engaged without once meeting in person? It takes several factors working together:

Relevance - Engagement begins by offering relevant content and learning activities. Learners need to value what they are learning and know that it can positively impact their work performance. From the start of the course, we introduce the WMO Competency Requirements for Education and Training Providers, and learners self-assess their current level of competence. This stimulates their curiosity and expectation for reward.

Materials are also designed for those new to the study of training as a discipline as participants are often assigned to the training based on their operational expertise or education level. While many complex topics are taught, such as needs assessment processes, learning assessment and the design of practical learning activities, the writing and discussion are kept to a level and length that avoid overwhelming learners with too much jargon and information. In addition, much of the content is provided in the form of worksheets and other takeaways that can be used on the job. In other words, some content is embedded in tools for application.

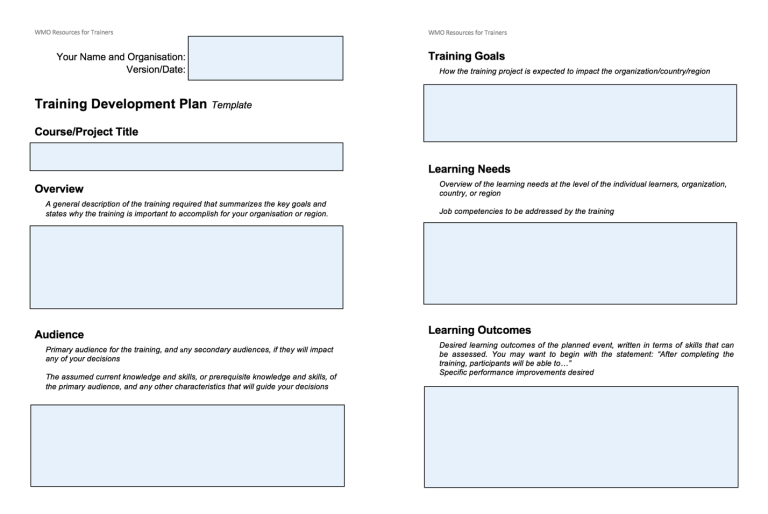

Project-based learning - The activity that has the most relevance is the creation of a Training Development Plan (TDP), based on a template provided at the start of the course. This assignment is the glue that ties the course together. The sections of the Plan correspond directly to the WMO Competencies, or subcomponents of them. (See Figure 1) While many will never have planned training using the method, all have had to make similar training decisions. Participants are asked to choose a training project in which they have been, are currently, or will soon be involved. The Plan is developed incrementally based on content and skills acquired in each unit and improved through continuous individual feedback from Coaches.

The TDP scope and length make this is a big assignment – often 10 to 20 pages long. However, the incremental production and feedback make it manageable for nearly all participants. To aid understanding of what is expected, example TDPs from past projects are shared for guidance, and a grading rubric describing expectations for each section is indicated. While the TDP is challenging, this challenge is one of the most successful engagement strategies. Effort that offers meaningful rewards is the first secret of engagement and motivation to follow through on lengthy tasks. The frequent reports that participants adopt the TDP into their work practice after the course demonstrates the relevance and reward.

|

Figure 1: Pages one and two of the Training Development Plan template used in 2019 |

|

|

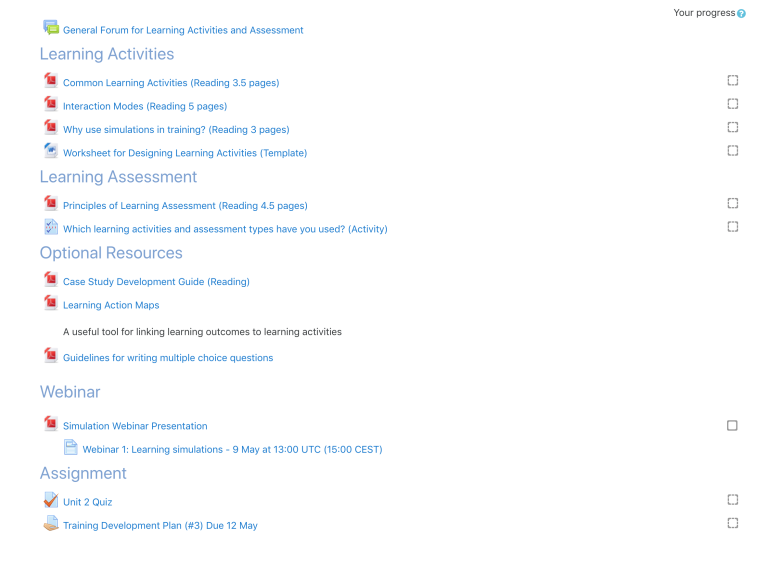

Figure 2: A portion of Unit 2 contents in the 2019 Online Course for Trainers |

Additional active learning approaches - The TDP project is just one active learning approach used in the course. Many people think of online learning as downloadable readings and recorded lectures, with occasional testing and opportunities for questions and answers, but such an approach would not exploit the potential of distance learning for teaching skills and knowledge and for sustaining engagement. Nearly any classroom activity can be replicated in some form online.

While the WMO Course for Trainers has both required and optional in-depth readings, these are not entirely passive. The readings often include reflection questions that become topics for discussion forums, examples to help ground the readings in practice, and accompanying worksheets or templates to help design instruction during and after the course. Each of the nine units includes at least one targeted activity that provides an opportunity for feedback to participants. A few popular examples include:

- Stories of most powerful learning experiences: At the start of the course, one “ice-breaker” activity asks each participant to share a powerful personal learning experience—either from a formal learning programme or an informal experience. This helps learners think critically about how we learn best.

- Visual presentation redesign: In a unit on design processes, with one part focused on visual design principles, participants follow guidelines to share a redesign of one of their instructional slide presentations, or a single complex slide from it.

- Using an online training simulation: After viewing an online weather forecast simulation (using a tool developed at EUMETSAT), participants are given a limited time to make a forecast decision using a variety of products.

- Sharing evaluation examples: Participants share and discuss surveys or other methods they have used to gain feedback from participants in their courses.

Clear and coherent design - The 9-unit course naturally contains many resources and activities, and its clear organization is critical to avoid confusion and intimidation. Moodle, the popular open-source virtual learning environment used to offer the course, allows the units to be displayed one unit at a time, but also offers a high-level overview of the entire course. Clicking on a unit reveals all resources and requirements for that unit/week. This tidy structure aids learners in their weekly planning.

Each unit is designed to be completed in approximately 6 to 8 hours and contains no more than 6 or 7 readings and activities, in addition to course project work. To clarify requirements, a unit introduction is made via a forum post or online video each week. This introduction links what is being learned from week to week and provides clear guidance on the unit requirements. While containing varied activities, each unit has a repeating basic structure.

The Moodle environment offers completion tracking so that learners have a visual indicator of their progress within a unit. Module summaries are offered at three points in the course to help learners feel a growing sense of achievement in what they have accomplished.

Recognition of Incremental Achievement

|

| Figure 3: An example unit open badge |

Regular structures provide a rhythm for learning, and a key element of that rhythm is regular recognition of achievements. So, in addition to check boxes for completion of each section, each unit offers a final quiz. The quizzes are not difficult, and are not a critical assessment element, but they demand that learners attend to all the course content. They can be retaken until a passing score is achieved, which motivates the learner to review content they missed or did not understand. Upon passing the Unit Quiz, the learner earns a digital badge for the unit. The nine badges are important incentives.

The Open Badge initiative promotes the use of such “micro-credentials,” a new trend in life-long learning for continuing professional development. Open, digital badges provide a more rigorous designation of accomplishment than certificates of attendance. Standards have been developed to allow badges to be collected from various training providers and to be stored in a personal “backpack” with metadata that describe how the badge was earned. The “backpack” can be used to provide evidence of skill development to managers and future employers. Open badges are a form of “gamification” of learning, that is the use of motivational methods found in games in non-gaming environments.

Regular communication and feedback

Online study can be lonely, especially for extroverted people. The course audience (all of whom are trainers) are often highly sociable by nature. Overcoming this potential downside of distance learning requires regular and open communication. If communication is too limited or too formal, distance is magnified. To bridge what is called the “transactional distance,” communication should be plentiful, welcoming, stimulating and helpful as well as respectful of time constraints.

From the beginning, principles of good online communication are taught, demonstrated and practiced. Each week there can be 100s of posts and responses to the unit discussion forums, beyond the assigned work. Course participants and facilitators appreciate the opportunity to interact with peers from other institutions and countries with similar professional responsibilities.

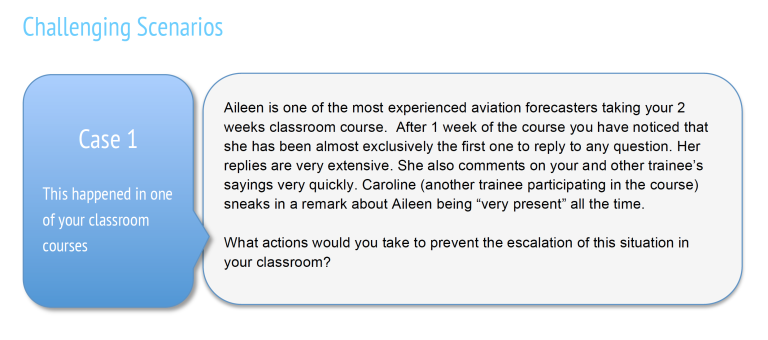

Each forum post generates an email to participants. Because this can become overwhelming, there is an option to receive a daily digest of posts in a single email, or to only read the forum posts when visiting the course website. To keep the discussions from becoming confusing, separate forums are used for general questions about the course (grading, schedules, etc.) and topic-oriented forums. In addition, some activities are operated as separate discussions with their own rules and structures. For example, the Facilitator’s Gym is a specialized forum in which participants suggest solutions to the problematic behaviors of students they might encounter in their courses. Each person reads a scenario of a problem situation, and then offers a solution a teacher might use. The solutions of other participants only become visible once a participant has submitted theirs.

The most important form of communication is feedback on performance in learning assignments. Without this critical communication, learning is diminished. Regular and timely feedback in a course this size requires quite a few facilitators. Thankfully, ETR has gathered a regular pool of volunteer facilitators with expertise that they enjoy sharing. The course has at times had as many as 20 active facilitators due to the number of participants and the emphasis on responding to forum posts within 24 hours. They are critical for the forums and course project – the TDP – that requires careful review and feedback. WMO has a Guide for Facilitators that helps those new to the role to prepare for the challenge of teaching online and providing good feedback and support. Grading rubrics for assignments are also provided.

|

Figure 4: A scenario for discussion in the Facilitator’s Gym |

Long-term impacts

A community of practice of trainers in WMO disciplines has formed over the years as a result of the course. Some stay in contact and join in other activities, for example, through the CALMet Community, which is closely aligned with the WMO Global Campus. Up to half of the volunteer facilitators are past course participants and all facilitators are part of the CALMet Community. Becoming a facilitator helps past participants to expand their knowledge and skills as a trainer and to offer their services to the international community. In this way, the course is continually renewed – new participants bring new questions and ideas, new facilitators bring new viewpoints. The course, with the social venue it offers for training professionals, has become a catalyst for growing the profession.

Another highly valuable outcome of the course is the WMO Trainer Resources Portal. All resources, worksheets, templates and examples used in the course over the years are now available on the Portal for anyone to access at any time, and for use in local courses.

Conclusion

The WMO courses for trainers have always strived to embrace new technologies and contemporary approaches to training practices. Just as WMO encourages the use of the most up-to-date technologies and procedures in service delivery among Members, it also encourages the adoption of contemporary educational technologies and techniques that have demonstrated effective outcomes and increased impacts for universities and professional training institutions. This is now paying off even more than expected, offering WMO advance preparation for the rapid transition to alternative delivery methods demanded by the current pandemic. The upcoming publication, WMO Global Campus Innovations, will highlight many additional approaches used by Members for their education and training initiatives.